On this page

- Departments (1)

- Pictures (2)

-

Text (10)

-

Untitled Article

-

Untitled Article

-

Untitled Article

-

Untitled Article

-

dDpm CmrariJ. *

-

Untitled Article

-

Untitled Article

-

Untitled Article

-

Untitled Article

-

Untitled Article

Note: This text has been automatically extracted via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software. The text has not been manually corrected and should not be relied on to be an accurate representation of the item.

-

-

Transcript

-

Note: This text has been automatically extracted via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software. The text has not been manually corrected and should not be relied on to be an accurate representation of the item.

Additionally, when viewing full transcripts, extracted text may not be in the same order as the original document.

Untitled Article

HERBERT SPENCER ON NATIONAL EDUCATION . Edward-street , Birmingham , March 10 , 1851 . ' " S ffi , —In a work recently published by Mr . Herbert Spencer on Social Statics , a chapter is devoted to the important question of national education , in which the author advocates the continuance of the present ineffectual no-system , and deprecates any interference on the part of the state whatsoever . On this chapter I would beg to make a few remarks , prefacing them with my thanks to Mr . Spencer for his very valuable addition to ethical science , and with the heartiest concurrence in most of the conclusions to which he has arrived , though almost entirely differing from him in this . One fatal mistake seems to pervade the whole chapter . National education is made synonymous with state-imparted education . Now , this is not necessarily and consequently the case . The one may be without the other . It by no means follows that because the state permits the people to tax themselves for the education of their children , that it shall be the schoolmaster , take up the ferule , and become a pedagogue . Further on Mr . Spencer asks , rather triumphantly , " What is education" ? The difficulties of furnishing a definition seem to have a sufficient argument for repudiating a national system . He continues , " what peculiar quality is there in reading , writing , and arithmetic , which gives the embryo citizen a right to have

them imparted to him ; but which quality is not shared in by geography , and history , and drawing , and the natural sciences" ? ( C . 26 , § 2 . ) I answer nothing at all . Education should embrace all these , and many more things . There may be , and is , great difference in respect to what a good education means . But all are agreed that each and every art and science are a part of education- In a national system I would include all the arts and sciences , leaving to the pupils the choice , after a good general primary education had been given , of learning those most to his taste , or most in accordance with his future association . Uut to me it seems a strange conclu sion that , because we differ in the definition of a good education , the people shall not receive any .

Our author next alludes to the narrow continental system , and endeavours to show by example the ill effects of national education . Here the mistake of confounding national with state educat on is again made . But , without demurring at thin , let us see if the facts adduced make out the case . l'Ynnce , and Austria , and Prussia , and China are given as examples of its power for destroying freedom and establishing kingly despotism and priestly rule . He say . , * as , from the proposition that Government ought to teach religion , there springs the other proposition that Government must decide what is religious truth , and how it is to he sought : bo the assertion that Government ought to educate necessitates the further assertion that it must say what education is , and how it shall be conducted . " ( C . ' 26 , § . ' { . ) The inference

from this is , that Government will train up the future population according to its own pattern , making in future generations a Hubservient and obedient population , ever ready to be the instrument of their rulers will , the tools of their rulem' caprice . The condition of tho peoples of the continent is adduced in proof of this . Now , I aflirm that experience in against our author here . Austrian people are not willing hIuvcs to the despotism which rules over them , and whose rule is canker to their hearts and wormwood to their tuateq ; The mighty Htandiug nrinieH required to keep them in subjection is proof of thiH . The attempts nuuU to thr' » w off the yoke are proof of this . Again , the ? i ' . / oplo of PruHbia are not willing ulaven to the weak , vacillating , dishonest Frederick Williiu" - Mr . Spencer , in Hinting the natural resultw of free , in opposition to state , or , aa ho eullw it , national

education , has drawn a true picture of the condition of the Prussian people even under their much-dreaded scheme . He says , " education , properly so-called , is closely associated with change—is its pioneer—is the never-sleeping agent of revolution—is always fitting men for higher things , and wifitting them for things as they are . " ( C . 26 , § 7 . ) Now , has not the education of Prussia done this ? In . the last attempts made there to gain a free constitution and to force the craven king to keep his oft-broken promises , were not the chief agents and actors men who had been educated in these very schools which our author so much deprecates ? And is it not one of the arguments made use of against the establishment of even

similar institutions , to say nothing of a true system of national education , in this country ; that they unfit men for the daily labour of life ; make them discontented with things as they are ; fill them full of revolutionary ideas ; in short , do all that Mr . Spencer says is the work of " education , properly so called ? " Now , if in Prussia , with its censor-ruled press , its want of any of the elements of popular government , such is the effect of the system there established , how much are we not justified in expecting from a freer and better system being established in this country , in which the press is comparatively free , and popular opinion one of the chief ruling powers ?

" How unfriendly , says Mr . Spencer , " all ecclesiastical bodies have been to the spread of education , every one knows . " ( C . 26 , § . 7 ) . Is not the opposition which such bodies ever presented to the establishment of national education in England , and the great obstacles they have ever thrown in the way , a strong reason in our favour ? There are many other things in the chapter , concerning which , did space allow , I should have been glad to have said a few words . The utter forgetfulness of the solemn unity of a national life , and the consequent importance that every member therein

should be educated , and the duty of society to see that such duty be fulfilled , manifested throughout the chapter is strange . The necessity laid upon the author to make every conclusion agree with his own beautifully simple premise , that * ' every man has freedom to do all that he wills , provided he infringes not the equal freedom of any other man" ( p . 2 , c . 4 , § 1 ) , has obscured for his rr . ind the fact that the ignorant man almost necessarily infringes upon the equal freedom of other men , and that to educate him is one of the chief means of making him capable of carrying out this our author's first principle . And nlan that it is idle to tell an uneducated man that he

has liberty to freely exercise all his faculties , when in such a state of ignorance it is impossible for him to do so . Trusting that in your proposed notice of the work of Mr . Spencer , to whom I again tender my thanks , you will more fully discuss this important question , Believe me , dear Sir , yours most truly , John Alf-ued IjAngpoiid .

Untitled Article

GOVERNMENT NOT A SUPERFLUITY . Cambo Morpeth , March 20 , 1851 . Sir , —In your review of that original , humanizing , and excellent work , Spencer's Social Statics , in No . 51 of your truly independent and highly intellectual paper , you say " as we think the function of Government is large , and that it is needed to govern society , as well as protect it . " Now , it appears to me that in the act of protecting society governing necessarily follows ; justice is the source of protection ; people inclined to injure their fellow-creatures will be prevented from doing so by just restraint , which restraint implies governing ; thus no explanation is needed to " govern society , " ap it naturally follows protection . Yours faithfully , AiiTiiiat TuKVii ^ YAW .

Untitled Article

7 , John-street , New-road , March 35 , 18 ') 1 . Sir , —In the Morning Advertiser of yesterdav , I find the following gratifying piece of intelligence , which , if you please , you may add to my last communication : —

" St . Marylebone Vestry , Saturday , March 22 , 1851 . — A report was brought up from the Oxford-street Committee , recommending the immediate removal of all the wood paving from that thoroughfare between Hegentcircus and Wells-street , oh account of its disgraceful and dans > erous state , and the substitution of granite cube paving . The report was unanimously adopted . " Singular enough , this is precisely the spot where so many accidents occurred , and to which I referred in my letter to the Morning Advertiser of Dec . 21 , and reprinted in your Journal on the 15 th instant . What makes the matter worse is , that there happened to

be several of the St . Marylebone vestrymen residing in the very street in front of whose doors so many animals laystretched and damaged vehicles scattered . The common dictates of humanity , as well as a proper sense of business as public men , one would suppose , would have induced the gentlemen , eyewitnesses as they must have been of the evils of this now universally admitted dangerous roadway , tu have taken public notice of it at their meeting on the following day ( Saturday ) . After a lapse of only three months , we at length behold these parochial M . P . ' s bestirring themselves in right earnest . Yours , &c , W . G .

Untitled Article

HEALTH OF LONDON DURING THE WEEK . ( From the Registrar-General ' s Report . ) The dcutliH registered in the Metropolitan districttTin the first three weeks of March were Huccestjivcly 1247 , 1401 , imd 1412 ; iu »< l in the last week tljey were 1118 . If the ten weeks of 1811-50 , coricBiionriing to lust week are taken for comparison , it appears that the lowest number occurred in the corresponding week of 18-12 , and wuh 8 o' 2 ; and that lite highest occurred in that of 1818 , and wait 1201 . The averse of tho ten wueks wan 107 < J , which , if corrected according t () tho assumed rate of increase in the population , namely l * fi /> per cent , annually , becomes

1171 . Last week ' s return , therefore , exhibits an excess on the estimated amount of ' 217 . Uut it it ; satisfactory to observe that thiH apparent incroiHe i . s nut due entirely to the complaints which Imve recently dwelled the weekly contributions of mortality . A number of casts on which coroners' iixjuesla have been held have been , ullowed to accumulate for » ome wct'ka , uml now at tho end of the quarter appear for the first time in the re ^ itttcrbookn . Small-pox continue *! to grow less fatal , and only 12 canes were registered hint week from this diueuHe . The births of ! M 7 boys and 8 . 'KJgirln , in ull 1780 children , were registered in the week . The average of 0 corrotmondiDK weeks in the years 1816 CO , was 1610 .

Ddpm Cmrarij. *

dDpm CmrariJ . *

Untitled Article

- [ IN THIS DSPARTMENT , AS ALL OPINIONS , HOWEVER EXTREME , ARK ALLOWED AN EXPRESSION , THE EDITOR NECESSARILY HOLPS HIMSELF RESPONSIBLE FOR NONE . ]

Untitled Article

There is no learned man but will confess he hath much profited by reading controversies , his senses awakened , and his judgment sharpened . If , then , it be profitable for him to read , why should it not , at least , be tolerable for his adversary to write . —Milton .

Untitled Article

April 5 , 185 lj 8 J > * . pLtAfe *? . 327

Untitled Article

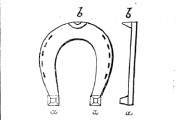

THE WOOD PAVEMENT . March 2 C , ISM . S IR > —As the feeling of noble indignation against cruelty to animals seems to be dormant , if not entirely extinguished , in the society for its suppression , and as the parishes in which wooden pavements are laid are prevented by certain contracts from ridding themselves of that most perfect of all unures laid for that most useful of all animals , the horse , it is but ju « t that persons who are neither vestrymen , nor exoflicio sympathizers with the suffering animals , should take the cause in their hands , and either , like Mr . W . < J alia way , point out the evil , and complain of the existence of such a pit-fall an the wood pavements become in frosty weather , or suggcHt means by which the evil could bo avoided in spite of the Haiti pavement being preserved . Allow me , tSir , to suggest , through your valuable Open Council , a remedy generally adopted in Poland , where ;—as is well known--the hornes are frequently obliged to cro .-s frozen rivers , lakes , or travel for hovituT hundred miles on snowy roads , which are rendered ho slippery by the traflic of HledgeH , that they become as smooth uh tf htHH , and yet the horscH never fall , becaune in winter they aie differently shod to what they are in summer . The difference between the Hummer and winter shoe i » , thut the latter has , besides the two heel-crooks , a , a , a , a tooth , b , b , at the top of tho

shoe , having almost the shape of an eye-tooth , which , with the two heel-crooks , forming a regular tripod , gives a firm footing to each of the four legs of the horse ; and , moreover , the sharpness of the tooth b prevents them from slipping .

There are some people in this country who think that the horses thus shod would wound themselves with the tooth of the shoe ; but that could only happen with horses who forge , i . e ., whose toes of their hind hoofs reach the fore-heels whilst trotting ; and , in such cases , which are exceedingly rare , the Poles only furnish the fore-hoofs with tooth shoes . The French winter shoes are riveted to the hoofs with nails having pointed and more protruding heads than , those used for the summer shoes , a remedy which is scarcely less inefficient than is the English roughshoeing . I am , Sir , your most obedient servant , A Poi . e .

Untitled Article

Effect of Emotion upon Senses . —I remember a lady whose mind is not very collected under excitements , at Ascot Races , looking anxiously to see the Emperor of Russia driven past , lie drove past a few yards from us . We had a capital sight of him ; but this lady saw nothing . She might as well have been at home . If emotions no blind the sense , how much more do thoy obscure the understanding ! When any interest or prejudioe ia stronger than the love of truth , truth will suffer . The blindness , b > th as regards the sense and the mind , often arises from our looking for something different from the fuct . And , again , we oft n invest an object with a form it has not , or evidence with conclusions forgone . How careful we should be to keep the mind steady and clear ! — Atkinson and Martineau ' s Letters on Man .

Untitled Picture

Untitled Picture

-

-

Citation

-

Leader (1850-1860), April 5, 1851, page 327, in the Nineteenth-Century Serials Edition (2008; 2018) ncse.ac.uk/periodicals/l/issues/vm2-ncseproduct1877/page/19/

-